Services in Kubernetes

Overview

Kubernetes [Pods] are ephemeral. They can come and go over time, especially when

driven by things like [ReplicationControllers]

While each pod gets its own IP address, those IP addresses can not be relied

upon to be stable over time. This leads to a problem: if some set of pods

(let's call them backends) provides functionality to other pods (let's call

them frontends) inside the Kubernetes cluster, how do those frontends find the

backends?

Enter services.

A Kubernetes service is an abstraction which defines a logical set of pods and

a policy by which to access them - sometimes called a micro-service. The goal

of services is to provide a bridge for non-Kubernetes-native applications to

access backends without the need to write code that is specific to Kubernetes.

A service offers clients an IP and port pair which, when accessed, redirects

to the appropriate backends. The set of pods targetted is determined by a label

selector.

As an example, consider an image-process backend which is running with 3 live

replicas. Those replicas are fungible - frontends do not care which backend

they use. While the actual pods that comprise the set may change, the

frontend client(s) do not need to know that. The service abstraction

enables this decoupling.

Defining a service

A service in Kubernetes is a REST object, similar to a pod. Like a pod a

service definitions can be POSTed to the apiserver to create a new instance.

For example, suppose you have a set of pods that each expose port 9376 and

carry a label "app=MyApp".

{

"id": "myapp",

"selector": {

"app": "MyApp"

},

"containerPort": 9376,

"protocol": "TCP",

"port": 8765

}

This specification will create a new service named "myapp" which resolves to

TCP port 9376 on any pod with the "app=MyApp" label. To access this

service, a client can simply connect to $MYAPP_SERVICE_HOST on port

$MYAPP_SERVICE_PORT.

How do they work?

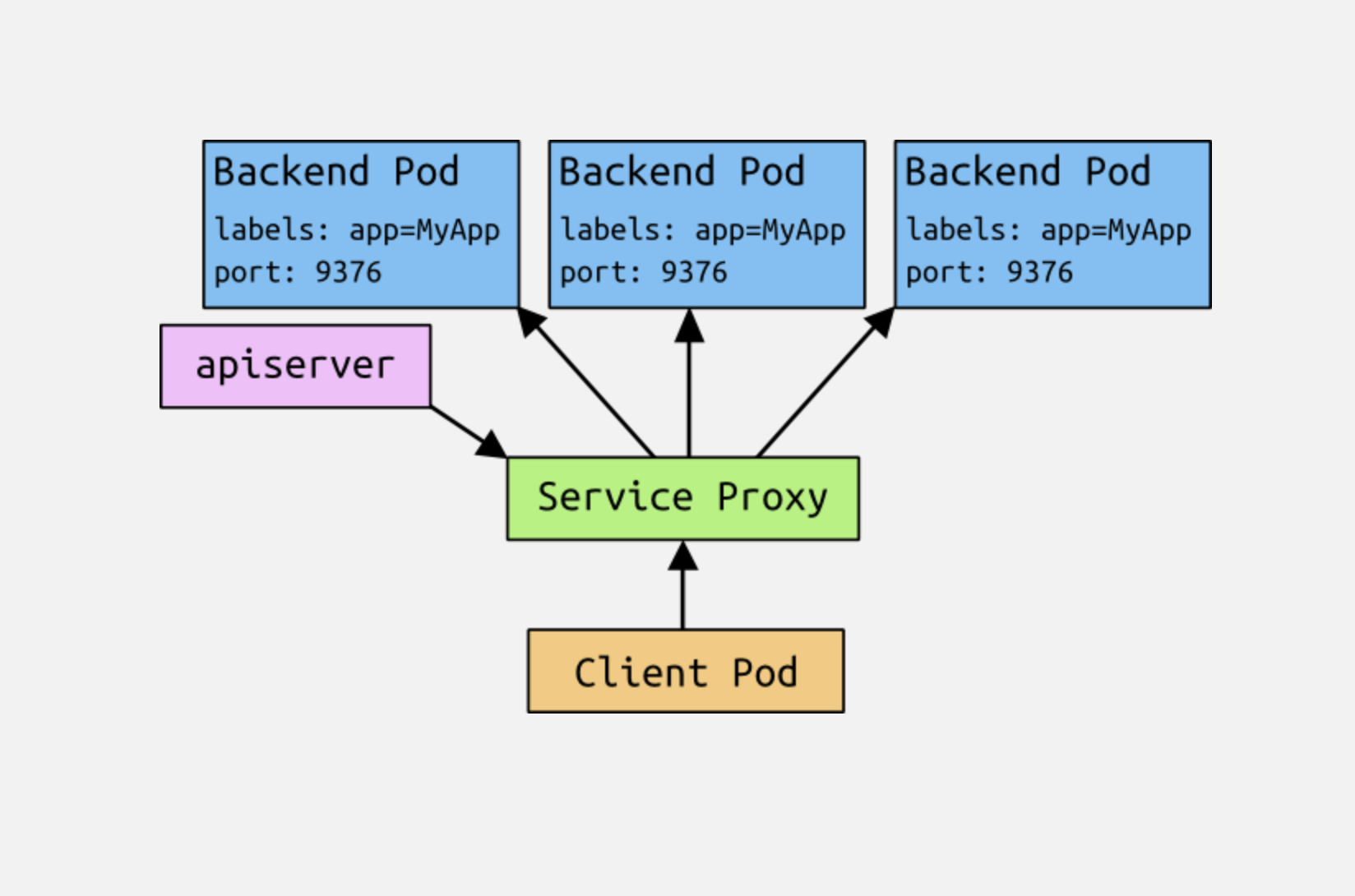

Each node in a Kubernetes cluster runs a service proxy. This application

watches the Kubernetes master for the addition and removal of service

objects and endpoints (pods that satisfy a service's label selector), and

maintains a mapping of service to list of endpoints. It opens a port on the

local node for each service and forwards traffic to backends (ostensibly

according to a policy, but the only policy supported for now is round-robin).

When a pod is scheduled, the master adds a set of environment variables for

each active service. We support both

Docker-links-compatible

variables and simpler {SVCNAME}_SERVICE_HOST and {SVCNAME}_SERVICE_PORT

variables. This does imply an ordering requirement - any service that a pod

wants to access must be created before the pod itself, or else the environment

variables will not be populated. This restriction will be removed once DNS for

services is supported.

A service, through its label selector, can resolve to 0 or more endpoints.

Over the life of a services, the set of pods which comprise that

services can

grow, shrink, or turn over completely. Clients will only see issues if they are

actively using a backend when that backend is removed from the services (and even

then, open connections will persist for some protocols).

The gory details

The previous information should be sufficient for many people who just want to

use services. However, there is a lot going on behind the scenes that may be

worth understanding.

Avoiding collisions

One of the primary philosophies of Kubernetes is that users should not be exposed to situations that could cause their actions to fail through no fault of their own. In this situation, we are looking at network ports - users should not have to choose a port number if that choice might collide with another user. That is an isolation failure.

In order to allow users to choose a port number for their services, we must

ensure that no two services can collide. We do that by allocating each

service its own IP address.

IPs and Portals

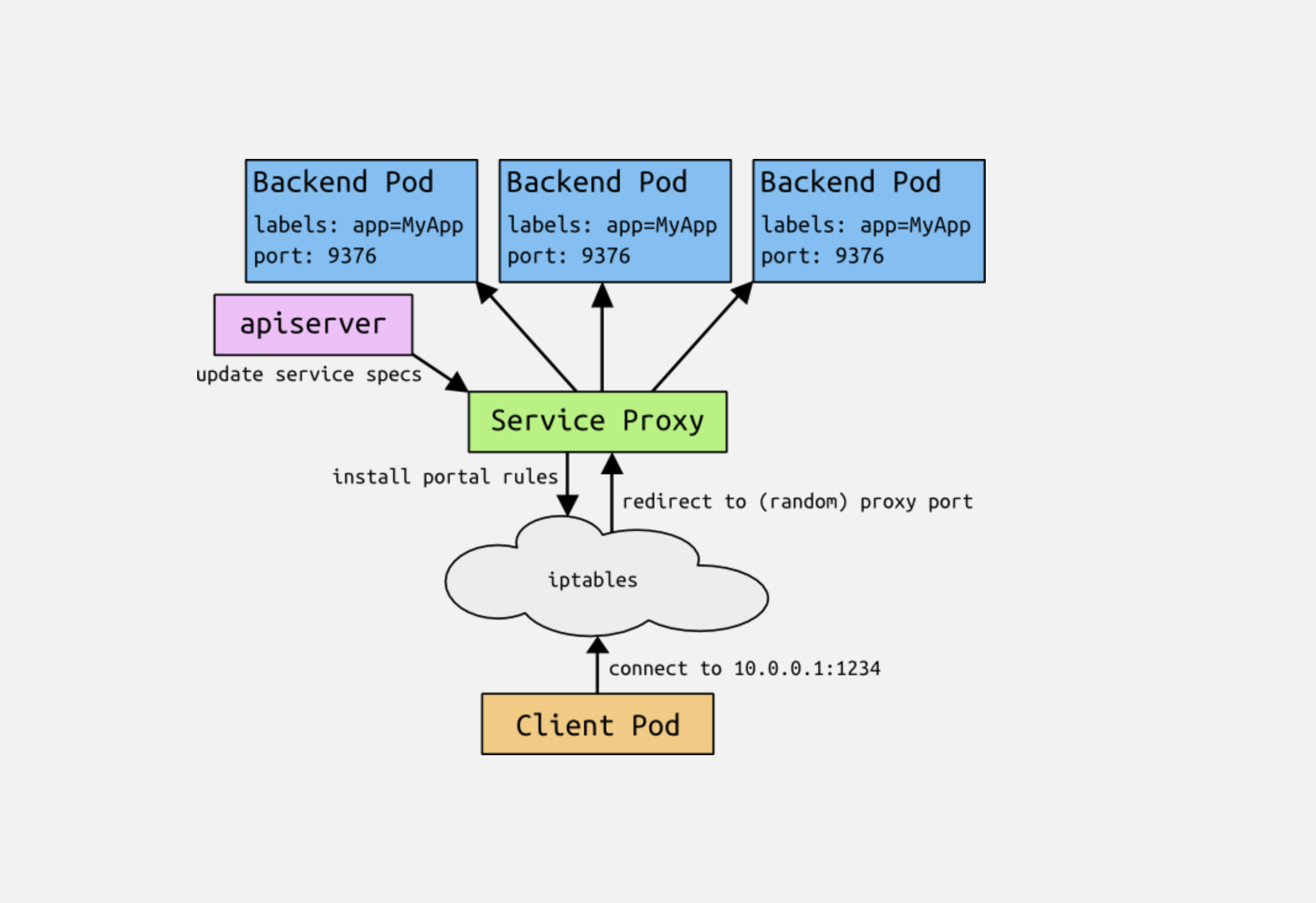

Unlike pod IP addresses, which actually route to a fixed destination,

service IPs are not actually answered by a single host. Instead, we use

iptables (packet processing logic in Linux) to define "virtual" IP addresses

which are transparently redirected as needed. We call the tuple of the

service IP and the service port the portal. When clients connect to the

portal, their traffic is automatically transported to an appropriate

endpoint. The environment variables for services are actually populated in

terms of the portal IP and port. We will be adding DNS support for

services, too.

As an example, consider the image processing application described above.

when the backend services is created, the Kubernetes master assigns a portal

IP address, for example 10.0.0.1. Assuming the service port is 1234, the

portal is 10.0.0.1:1234. The master stores that information, which is then

observed by all of the service proxy instances in the cluster. When a proxy

sees a new portal, it opens a new random port, establish an iptables redirect

from the portal to this new port, and starts accepting connections on it.

When a client connects to MYAPP_SERVICE_HOST on the portal port (whether

they know the port statically or look it up as MYAPP_SERVICE_PORT), the

iptables rule kicks in, and redirects the packets to the service proxy's own

port. The service proxy chooses a backend, and starts proxying traffic from

the client to the backend.

The net result is that users can choose any service port they want without

risk of collision. Clients can simply connect to an IP and port, without

being aware of which pods they are accessing.

Shortcomings

Part of the service specification is a createExternalLoadBalancer flag,

which tells the master to make an external load balancer that points to the

service. In order to do this today, the service proxy must answer on a known

(i.e. not random) port. In this case, the service port is promoted to the

proxy port. This means that is is still possible for users to collide with

each others services or with other pods. We expect most services will not

set this flag, mitigating the exposure.

We expect that using iptables for portals will work at small scale, but will not scale to large clusters with thousands of services. See the original design proposal for portals for more details.

Future work

In the future we envision that the proxy policy can become more nuanced than

simple round robin balancing, for example master elected or sharded. We also

envision that some services will have "real" load balancers, in which case the

portal will simply transport the packets there.

PR # 1402

当创建一个服务时,我们从一个特殊的IP范围分配一个IP。这个IP是门户IP。我们将此服务及其端口号广播给所有(每个仆从一个)kube-proxy实例以及Portal IP。kube-proxy设置iptables规则,将流量“窃取”到Portal [IP,端口],并将其重定向到随机/临时端口上的自身。kube-proxy充当大使(与今天一样),并将在服务的组成部分之间循环传输流量。

服务添加了 PortalIP 和 ProxyPort 两个字段 ,创建服务时候由 master 来分配, 准确来说是 portalMgr.AllocateNext()

Proxy 服务使用 iptables 的方式来分发流量,因此每台机器上只需要一个 proxier。

代码讲解:

// OnUpdate manages the active set of service proxies.

// Active service proxies are reinitialized if found in the update set or

// shutdown if missing from the update set.

func (proxier *Proxier) OnUpdate(services []api.Service) {

glog.V(4).Infof("Received update notice: %+v", services)

activeServices := util.StringSet{}

for _, service := range services {

activeServices.Insert(service.ID)

info, exists := proxier.getServiceInfo(service.ID)

serviceIP := net.ParseIP(service.PortalIP)

// TODO: check health of the socket? What if ProxyLoop exited?

if exists && info.isActive() && info.portalPort == service.Port && info.portalIP.Equal(serviceIP) {

continue

}

if exists && (info.portalPort != service.Port || !info.portalIP.Equal(serviceIP)) {

glog.V(4).Infof("Something changed for service %q: stopping it", service.ID)

err := proxier.closePortal(service.ID, info)

if err != nil {

glog.Errorf("Failed to close portal for %q: %s", service.ID, err)

}

err = proxier.stopProxy(service.ID, info)

if err != nil {

glog.Errorf("Failed to stop service %q: %s", service.ID, err)

}

}

glog.V(1).Infof("Adding new service %q at %s:%d/%s (local :%d)", service.ID, serviceIP, service.Port, service.Protocol, service.ProxyPort)

info, err := proxier.addServiceOnPort(service.ID, service.Protocol, service.ProxyPort, udpIdleTimeout)

if err != nil {

glog.Errorf("Failed to start proxy for %q: %+v", service.ID, err)

continue

}

info.portalIP = serviceIP

info.portalPort = service.Port

err = proxier.openPortal(service.ID, info)

if err != nil {

glog.Errorf("Failed to open portal for %q: %s", service.ID, err)

}

}

proxier.mu.Lock()

defer proxier.mu.Unlock()

for name, info := range proxier.serviceMap {

if !activeServices.Has(name) {

glog.V(1).Infof("Stopping service %q", name)

err := proxier.closePortal(name, info)

if err != nil {

glog.Errorf("Failed to close portal for %q: %s", name, err)

}

err = proxier.stopProxyInternal(name, info)

if err != nil {

glog.Errorf("Failed to stop service %q: %s", name, err)

}

}

}

}

- 首先,遍历传入的所有服务。对于每一个服务,检查是否存在一个活动的、与服务配置相匹配的代理。如果存在并且配置没有变更,则继续处理下一个服务。

- 如果服务存在但配置已变更,或者服务不存在,那么需要做出响应。对于配置已变更的服务,先关闭其对应的iptables入口(通过

closePortal方法),然后停止服务代理。然后,对于新的服务或配置已变更的服务,创建新的服务代理并打开iptables入口,以将流量重定向到新的服务代理。 - 处理完所有传入的服务后,检查Proxier是否存在任何多余的服务代理(即不在新的服务列表中的服务代理)。如果存在,关闭其iptables入口并停止服务代理。

这个函数的目标是确保Proxier的状态和Kubernetes的服务状态同步。即,在任何时刻,Proxier应该为每一个Kubernetes服务运行一个和服务配置相匹配的代理,并且仅为此运行代理。

这段代码中涉及的iptables操作(通过openPortal和closePortal方法)是用来将网络流量导向特定服务的代理。具体来说,openPortal创建的iptables规则将目标为服务IP和端口的流量重定向到代理的IP和端口,而closePortal删除的iptables规则则停止这种重定向。